Courtyard Block Essentials

What are the essential components of a courtyard block and buildings; How courtyard blocks differ from other block and courtyard forms; Why it matters

This is the article to share with owners, developers, architects, municipalities—anyone who needs an essential guide to courtyard urbanism. There are four sections to this article, corresponding with the four components of successful courtyard blocks:

Small-Lot Buildings—A courtyard block is framed with multiple, small-lot buildings; a courtyard block is not a mega-development.

Wide and Shallow Buildings—Courtyard block buildings are wide and shallow, with no front or side setbacks; this form is essential for creating private courtyards and dual-aspect units with excellent light and ventilation that “live like a house.”

Mixed-Use Buildings—Courtyard block buildings should be mostly mixed-use, with commercial on the bottom and residences on top; commercial integration is essential to creating walkable, convenient neighborhoods where daily needs are met close to home, reducing car dependence and increasing community-oriented street life.

Unit Diversity—Courtyard block buildings include a mix of large (3-4BD+) and small (studio, 1-2BD) units within each building to accommodate households of different sizes and incomes, fostering inclusive, multigenerational communities with organic affordability.

1. Small-Lot Buildings—A courtyard block is framed with multiple, small-lot buildings; a courtyard block is not a mega-development.

People sometimes tell me that we already have courtyard apartments in the USA, and they send me pictures of a courtyard mega-development like this, from Plano, Texas:

Looks like a nice courtyard, especially if your kids are strong swimmers.

As we can see from the aerial view and building floorpans, this is a mega-development. The courtyard is enclosed by a single structure that is very large. The units are all small and accessed via a network of corridors that run circuits inside the building. The entire building is surrounded by parking lots.

There are 264 units in this particular mega-development. A mix of studio, 1BD, and 2BDs. It also includes a gym, sauna, pet area, some commercial areas, among other amenities that add cost. At ~$250-$300/unit to build, this was likely a $60-70M project.

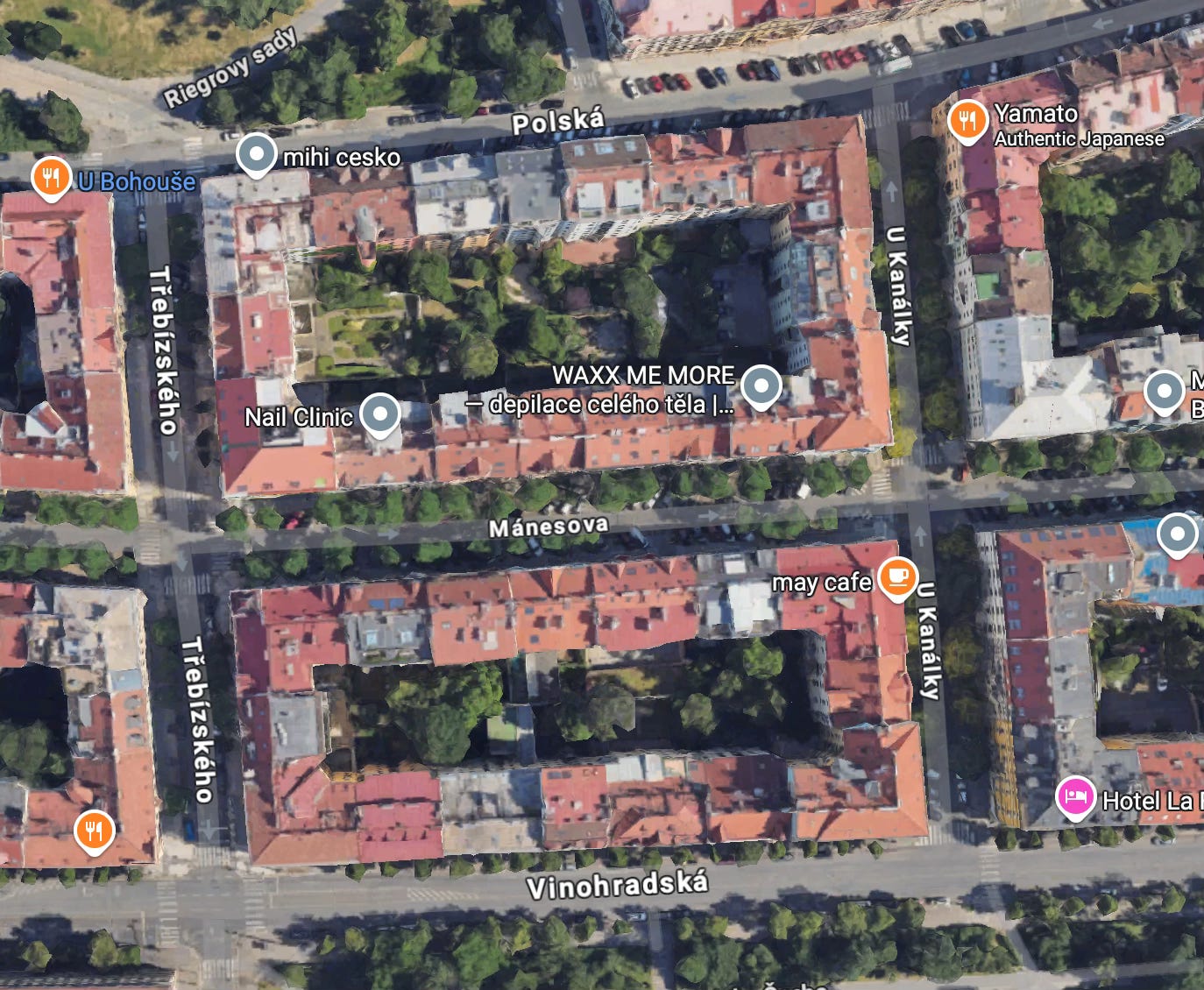

Now let us look at small-lot courtyard blocks in Prague and Oslo. The courtyards here are not designed as part of a single mega-development—they emerge organically from the way individual buildings are constructed around the block.

Notice how these courtyard blocks in Prague and Oslo are made up many different buildings that are joined together to form a perimeter wall enclosing a central courtyard:

The buildings achieve a similar floor area as the mega-development, but the floor area is chunked into 10-20 smaller buildings.

Why build a courtyard block of small-lot buildings instead of a courtyard mega-development?

Lower Cost & Risk, Broader Participation:

Small-lot buildings are lower cost to build not just because they are smaller in size, but because they typically don’t require elevators (or only small ones), underground parking, luxury amenities, or the expensive materials associated with larger developments.

The smaller and simpler buildings reduce both upfront and long-term costs, making the resulting units more naturally affordable. A 20,000 sqft, 4 story building might cost between $4-6M to building, depending on elevator and parking infrastructure as well as local construction costs.

Smaller-scale projects distribute financial risk and open the door to a wider range of builders, including small developers, community groups, and even homeowner-developers.

Instead of one national mega-developer building a $60-$70M project, you might have 15 local developers or community groups building 15 $5M projects.

Better Social Scale: People tend to feel more at ease in smaller multifamily buildings, where they share entrances, stairwells, and common spaces with a limited number of households—typically just 5 to 10, rather than dozens or hundreds.

This “scale of sociability” strikes a balance between privacy and community: residents are more likely to recognize neighbors, build trust, take shared responsibility for common areas, and feel a greater sense of personal security.

In contrast, large buildings can feel impersonal and overwhelming, often leading to social isolation and weaker community bonds. A smaller social scale is especially valuable for young parents, who want to know everyone their kids might encounter in shared spaces.

Better Streets and Blocks: Small-lot courtyard buildings create a visually interesting street wall and block structure. They create the horizontal and vertical density and diversity that is the stuff of beautiful and sustainable urban fabric.

By contrast, mega developments often have monotonous and dead street walls that deter pedestrians and community interaction.

Even mega-developers know that people crave small-lot urbanism, and sometimes they use granular, small-lot facades to mask mega-developments:

In short, small-lot buildings are essential to courtyard urbanism because they enable low-cost development; foster a socially comfortable scale; and create active and attractive streets and neighborhoods.

2. Courtyard Building Format (wide and shallow, no front or side setbacks)

This building form is essential for two key reasons:

it creates the perimeter block conditions necessary for a tranquil, private courtyard amenity

it allows for dual-aspect “lives like a house” units with excellent natural light and ventilation.

Both the private courtyard and the dual-aspect, or front-to-back, units create multi-family units that “live like a house.” This is how we give Americans a “big house with a yard” but in the dense city center, with all the amenities and conveniences of urban life.

To understand how this building form supports courtyard living, let’s compare it with typical American city buildings and lots.

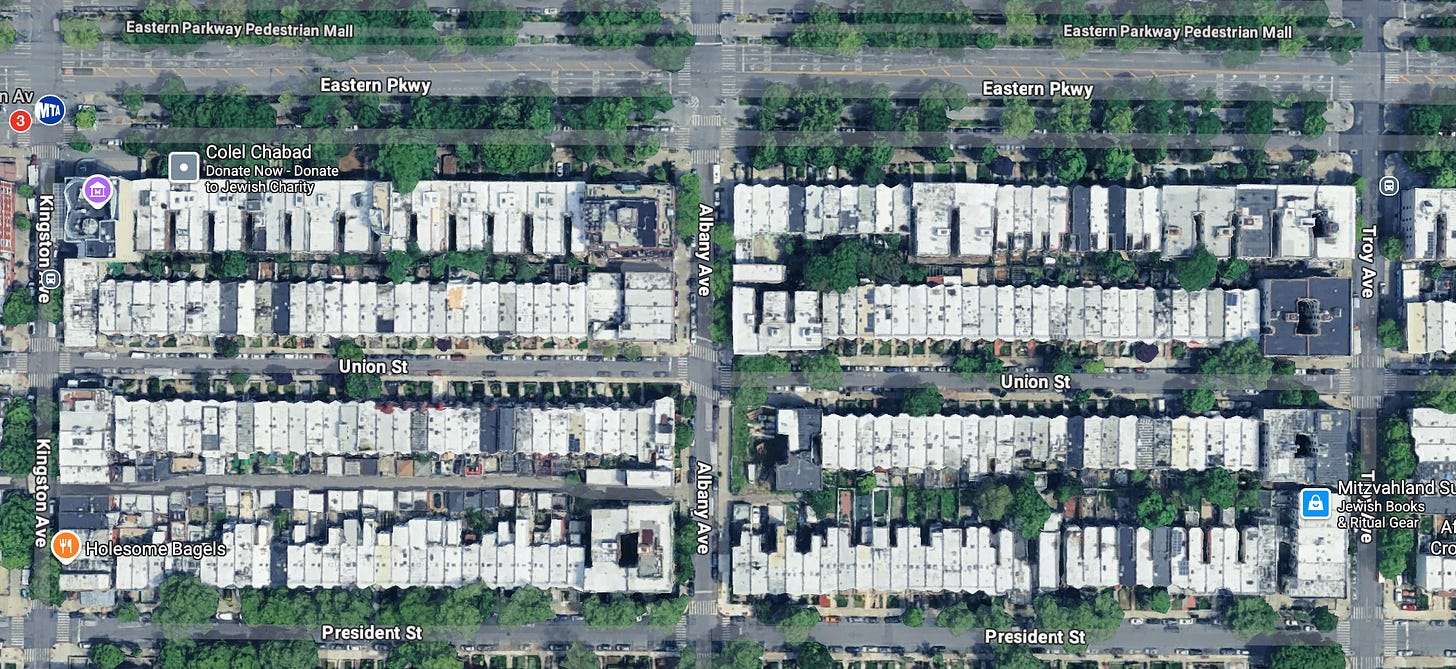

Take Brooklyn row houses from the 1800s, pictured below. These single-family homes share walls with neighbors but sit on long, narrow lots, making the short sides of the rectangle the primary window walls. This design results in poor light and ventilation in the center of the building. Additionally, these homes have front setbacks, causing buildings to extend deep into the lot and leaving very little usable green space in the block interior.

Here is a Redditor asking for help with the challenging interior design for her narrow row house:

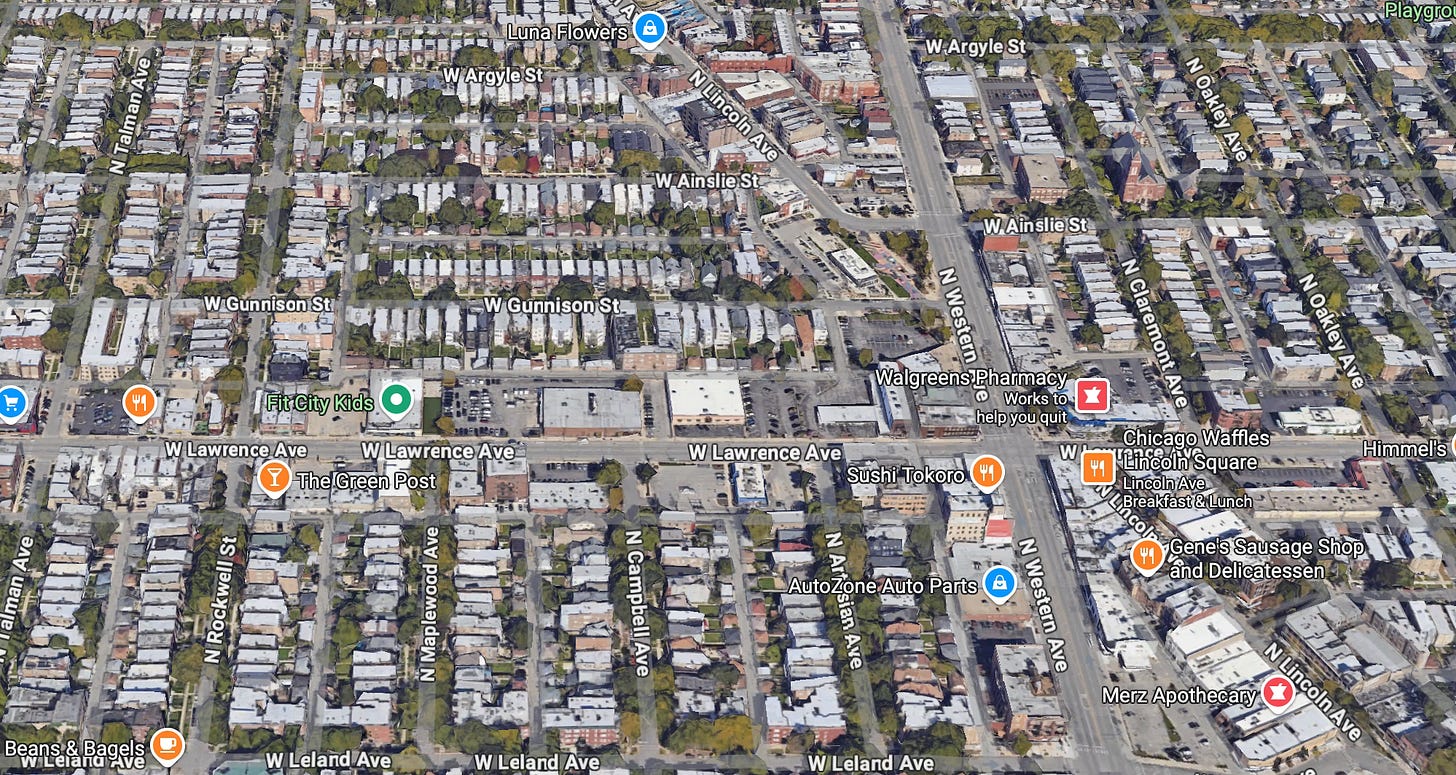

Now, consider St. Louis (below), which resembles Chicago in having alleys that provide access to garages at the rear. The lots are narrow and deep, typically 25’x125’ as they are in Chicago. The buildings are mostly freestanding or slightly detached, set back from the street, and extend deep into the lot. The alleys and setbacks make the block porous, allowing noise, cars, and other disturbances to penetrate easily from the street into the interior. As a result, there is almost no usable yard space, and no continuous building perimeter to shield the block’s private interior.

If you look at many legacy American cities or London, where our city block form comes from, you’ll see this pattern repeated: squat, narrow, deep homes with minimal organization of a strong building wall that separates the exterior from the interior of a block. Here is my Chicago neighborhood:

Now, contrast the traditional US city block with the perimeter blocks common in continental Europe, Scandinavia, and, curiously, Scotland.

Look at Prague’s blocks. The standard buildings are mixed-use, multi-family buildings with 8-10 units above commercial spaces. They are wider (about 50 to 60 feet of street frontage) but shallow (40-50 feet), leaving more green space in the back.

These buildings have no side setbacks and are built wall-to-wall with “party walls” (blank side walls) that join adjacent buildings. There’s also no front setback: the shallow building goes right up to the property line, preserving a large green space at the back of the lot.

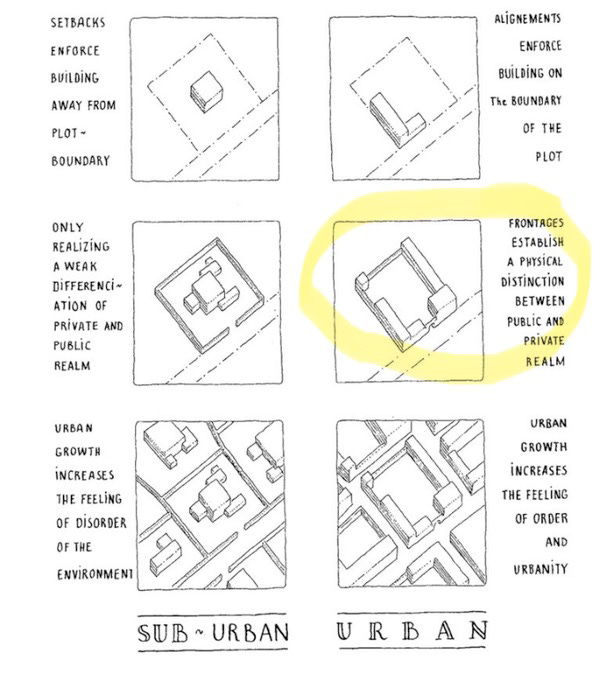

By concentrating building mass wide, shallow, and tall around the block’s perimeter, this design passively creates a physical distinction between public and private realm, a distinction that the architect and writer Leon Krier regarded as essential to the urban form:

The valuable semi-private courtyard amenity is, again, a passive consequence of wide and shallow building design with no front or side set backs.

Importantly, these blocks achieve greater green area even as they achieve higher density levels due to their height and efficient use of the greater area around the perimeter of the block. For example, central Prague’s density is about 33,000 people per square mile, while a North Side Chicago neighborhood might have 23,000 people per square mile: fewer residents and less green space because of different building mass distribution.

In addition to creating a green courtyard amenity, the wide and shallow building is also key to creating dual-aspect units that “live like a house,” with windows facing both the street and the courtyard. These units enjoy the convenience and vibrancy of the public street out front and a quiet, private “backyard.”

Most large multifamily buildings in the U.S. lack these dual-aspect units, which may partly explain the American stigma against apartments. For example, in the Plano, Texas courtyard mega-development, the developer builds segments of the building very deep, with a central corridor and units on both sides—a “double-loaded corridor.” This layout means units face either the street or the courtyard but never both. As a result, these units lack the front-to-back light and ventilation, and the elegant, home-like layouts common in European multifamily housing.

Their size and layouts are constrained by the limited window wall, and the units “live like a hotel” or dormitory, rather than a house, due to the corridors and the large scale of the building.

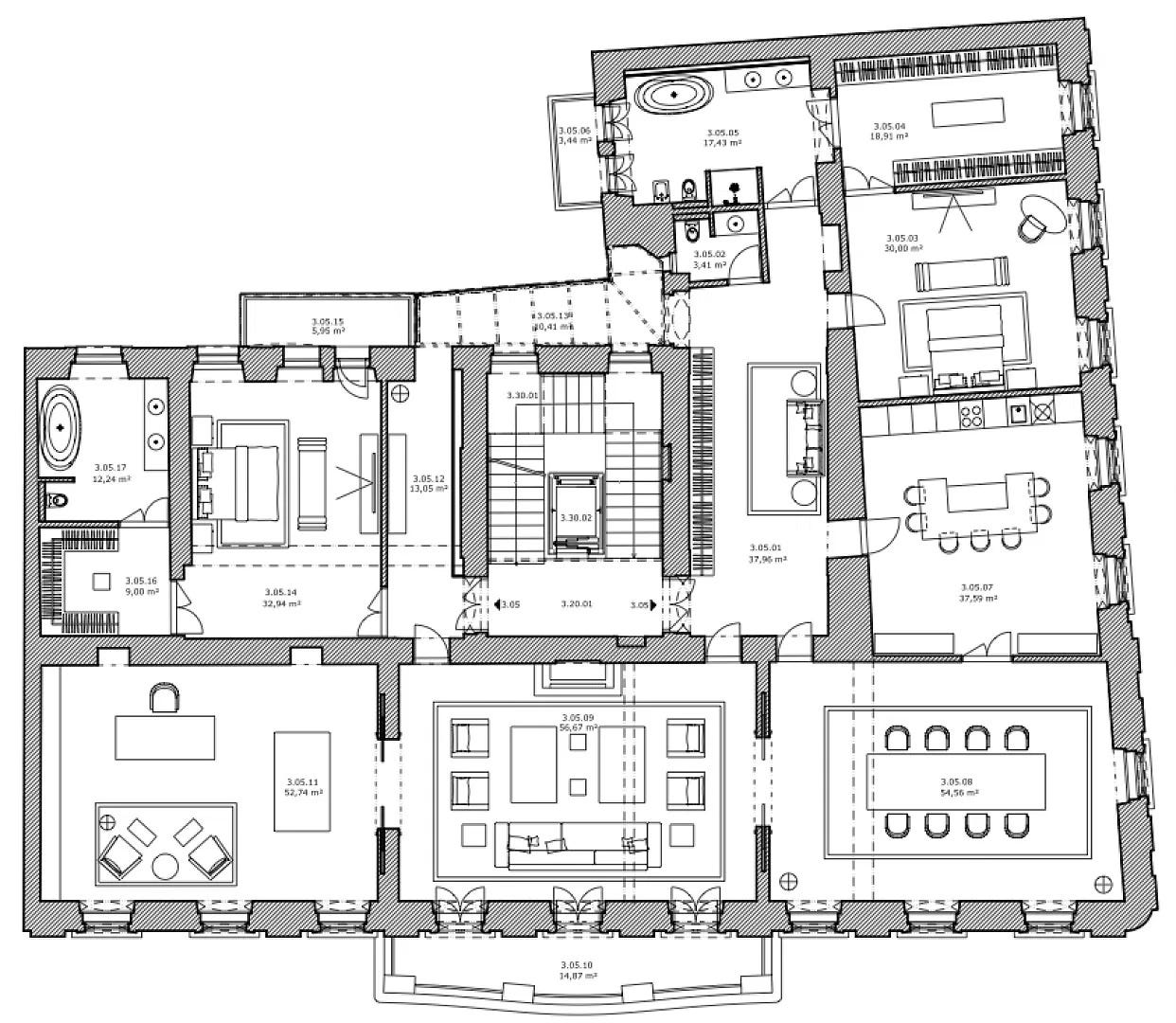

Now, let us compare with unit layouts and rooms that are possible in the wide and shallow building, with window walls in the larger units that extend along the width of the building. Here is a 4BD in Prague:

Here is a picture of the living rooms from that apartment:

Most courtyard apartments in these cities are not 4BD. Most are smaller. But the wide and shallow floorplate creates the conditions for large units as well as smaller units. Here are more interior photos from courtyard buildings in Edinburgh, Stockholm, and Copenhagen:

Because the long sides of the rectangle are window walls (instead of the narrow sides, as in row houses), the wide and shallow courtyard apartment has excellent light, ventilation, and gracious room layouts.

For parents, having a window overlooking a secure courtyard makes it feasible to care for a young child playing outside while inside preparing meals, putting the baby down, or even working.

In sum, the shallow and wide courtyard building is essential to creating the valuable semi-private courtyard as well as the units that“live like a big house with yard” thanks to the generous proportions and the excellent lighting and ventilation.

3. Mixed-Use Buildings: Maximizing Walkability and Daily Convenience

Mixed-use buildings are essential for creating walkable neighborhoods that put people in close proximity to shopping, friends, school, and a million other uses and destinations.

In the most valuable, high-demand districts of major European and American cities, mixed-use buildings are the norm: commercial spaces on the ground floor, residences above. This co-location of uses creates lively streetscapes and unparalleled convenience.

By contrast, most American cities are mono-zoned, separating residential from commercial. Even in my own Chicago neighborhood—labeled a “walker’s paradise” by WalkScore.com—I have to walk a third of a mile just to reach a grocery store. That’s workable, but it doesn’t come close to the level of convenience I experienced in European courtyard block neighborhoods, where every block includes dozens of businesses at street level.

Integrating commercial space into new housing is a challenge in today’s U.S. real estate environment. We lack a strong tradition of mixed-use development, and many retailers continue to prefer drive-to box stores. It’s unclear exactly how leasing ground-floor commercial space in new courtyard block housing will take shape in the U.S. market. In cities like Berlin and Paris, commercial real estate is stronger in part thanks to local policies: governments subsidize small businesses and limit the presence of auto-oriented retail within city limits.

This is a problem that requires collaboration across sectors. Real estate brokers, city officials, lenders, and business owners all have a role to play. The payoff is huge. Americans consistently show strong preference for walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. And we now know what the housing form looks like to support that lifestyle. What’s needed is a broad coalition of public and private players to bring familiar, beloved businesses into these more compact and connected neighborhoods.

The benefits of mixed-use buildings are tangible and immediate. The parent who needs to grab groceries, a coffee, an antibiotic for a sick child, or a six pack, can walk downstairs to the corner store, pharmacy, or café. When commercial and residential life are collocated, courtyard block neighborhoods become some of the most walkable and least car-dependent places to live. Less time spent driving, lower transportation costs, and more time (and money) rooted in local community.

4. Unit Diversity: A Foundation for Social Cohesion and Natural Housing Affordability

Buildings that include a range of units promote social cohesion and sustainable family life. Their scale allows for natural income diversity—a mix of larger, higher-value units and smaller, lower-cost ones—without requiring formal subsidy.

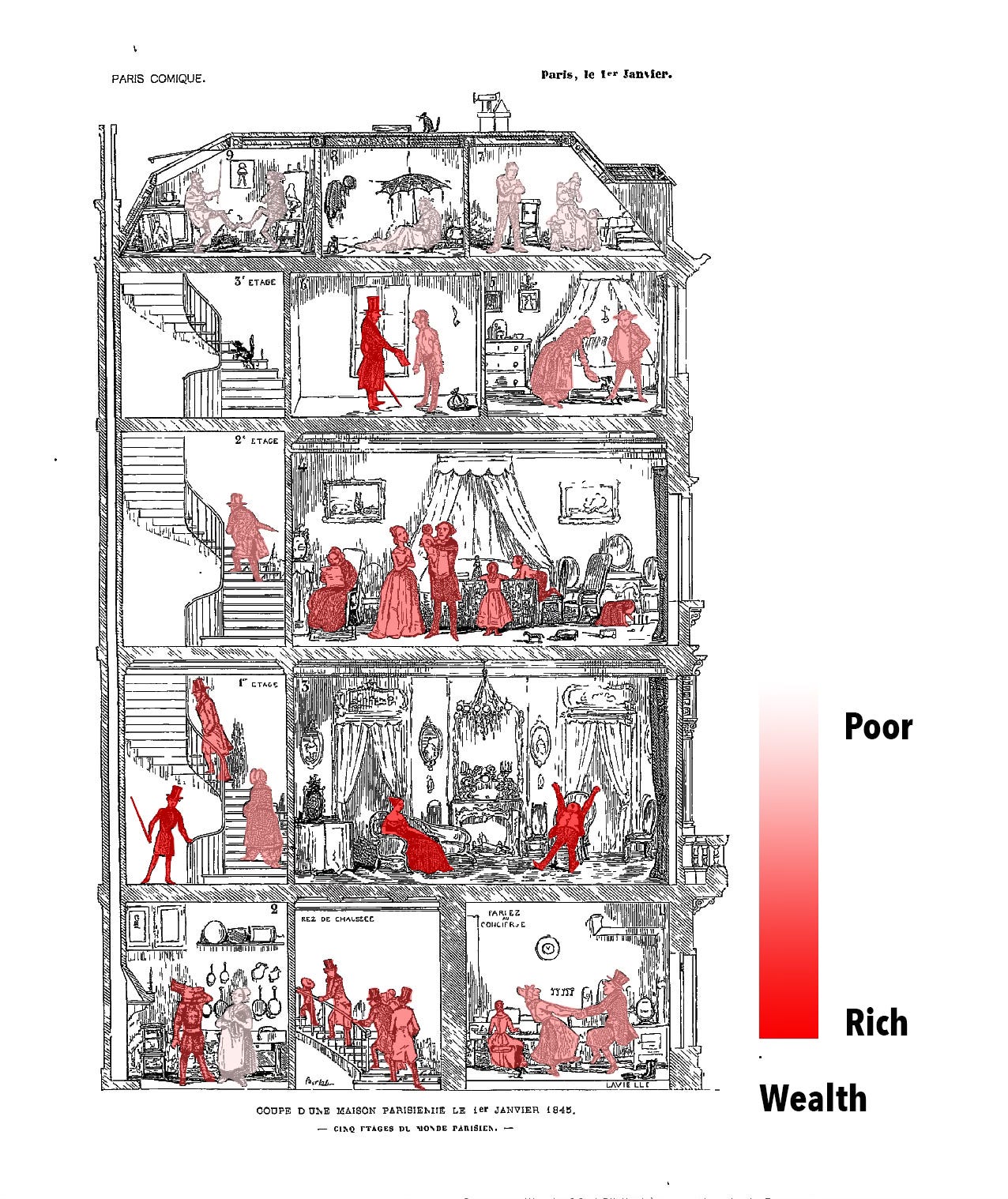

In many traditional courtyard blocks, this income diversity happens vertically. Larger, higher-end units are typically located on the lower floors, offering easier access to the courtyard and street—ideal for families or older residents. Upper-level units, especially in buildings without elevators, tend to be smaller and far more affordable. These walk-up studios or one-bedrooms are often perfect for students, young professionals, or others looking for low-cost urban housing. Because they share land, utility, and maintenance costs with residents of more expensive units and with ground-floor businesses, these units can remain naturally low-cost without sacrificing quality of life.

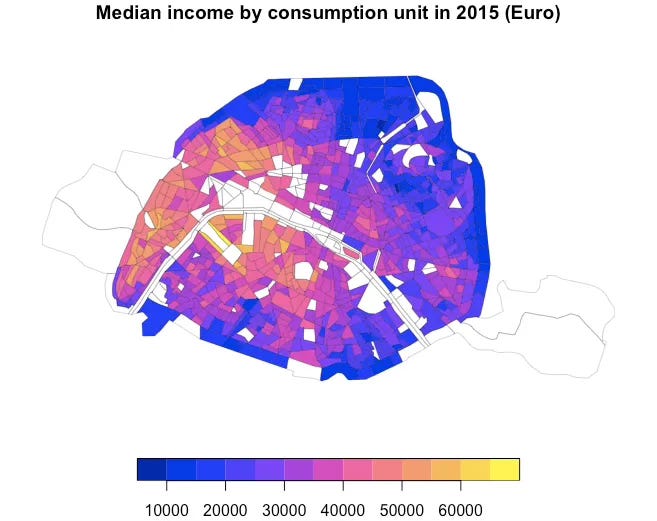

Mixed-income courtyard blocks are the norm in many Scandinavian, French, German, and Italian cities. A 19th-century illustration famously shows the vertical distribution of wealth in Parisian apartment buildings—from the affluent on the lower floors to the working class in the upper walk-ups:

Mixed-income buildings can help counteract the spatial segregation common in many American cities. A Parisian blogger living in San Francisco noticed that American urban neighborhoods tend to be very rich or very poor, while Paris had greater income diversity. He made a map to visualize the smoother income gradients in Paris:

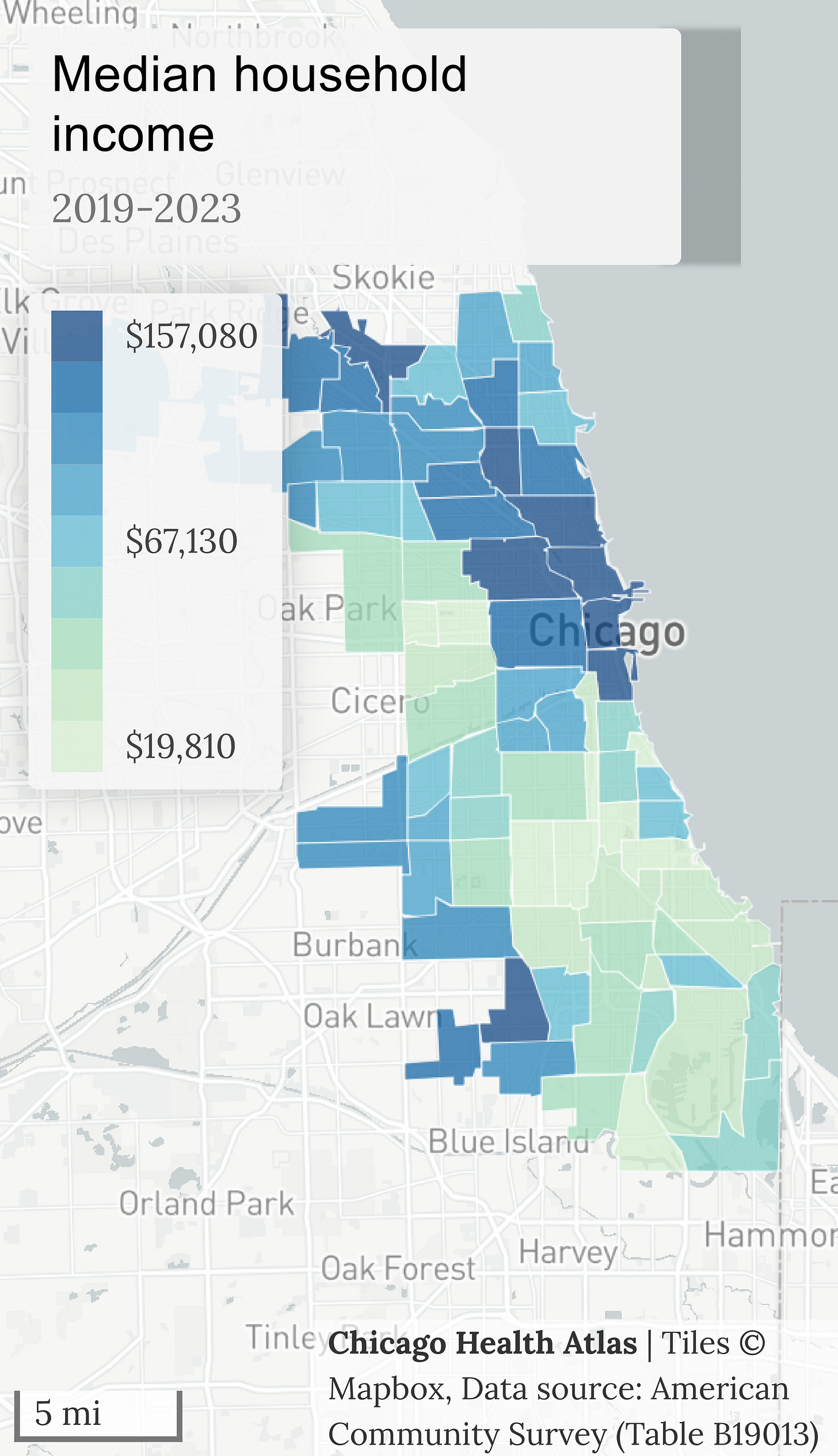

Chicago, by contrast, has not had a strong tradition of mixed-income housing. Income differentiation tends to manifest horizontally, across neighborhoods and community areas, leading to homogeneously rich or poor neighborhoods.

In the U.S., patterns of multifamily and single family development have separated us by income and by age. Childless adults live in one kind of housing and neighborhood. Young families go in another. Seniors are often clustered separately. But this compartmentalization makes mutual support much harder. When people of different ages and incomes share buildings and blocks, informal support networks naturally emerge: families benefit from living near dog-walkers, babysitters, tutors, and grandparents; local businesses thrive on a steady and diverse stream of customers drawn from the immediate neighborhood.

All of this speaks to the courtyard block as a powerful tool for multigenerational living and community cohesion. I often talk about building “complete life cycle” cities where people can grow up, raise families, age in place, and stay rooted for generations. European cities have achieved this through centuries of mixed-use, small-lot perimeter blocks. American cities, by contrast, have always struggled to maintain population, and their failure to build amenity-rich, family-friendly density has pushed population and revenue to sprawling suburban counties.

That failure is not inevitable. It’s a product of our badly designed built environment. To build cities that can truly support a complete demographic, we need better buildings to create better streets, blocks, and neighborhoods.

Conclusion

This article lays out what I hope is a clear blueprint for building better cities through courtyard block design. Unlike sprawling mega-developments, true courtyard blocks are formed by multiple small-lot, wide-and-shallow buildings that wrap around shared green space. This format supports dual-aspect units with excellent natural light, ventilation, and a home-like feel. Mixed-use buildings foster walkable, convenient neighborhoods, while unit diversity within buildings enables multigenerational, mixed-income communities to thrive organically. Together, these four elements—small-lot development, shallow building footprints, commercial-residential integration, and unit variety—create a more affordable, sociable, and sustainable urban fabric. For policymakers, architects, and developers alike, this approach offers a viable path toward flourishing and expanding neighborhoods where people of all ages and incomes can live, work, and grow together.

Alicia, something I’ve been wondering is if courtyard blocks work at a lower density level I.e. 2-3 stories? In theory I imagine it would be quite easy to use the American rowhome and just eliminate the setbacks and create the courtyard. But with that would come the long and skinny floor plan that you promote against. My question then is does it make sense/how would it work to have the wide and shallow courtyard blocks but at 2-3 floors instead of 6ish? I’m thinking for further outside of a city center so people could get more of a “quieter” feel but still enjoy the courtyard block style or near suburban downtowns. Thanks!

Fantastic article. It encapsulates perfectly the issues with monozone urban planning, as opposed to the developed forms of urban systems in the Old World. Everything, from lifestyle, through to architecture, social aspect, urban efficiency and even conveniences of urban living are all encapsulated in the courtyard design, which I noticed is wholly absent from new developments.

In order to make the transition however, it will have to be pioneered by one brave developer, who can put money down for a traditional development and turn a profit on it, to show others what actually sells, as opposed to the same old megablock monstrosities. I bet it would sell better than the new style housing too, but that’s just my hunch.

Again, great article.